Typically I eschew today’s news. As far as I’m concerned, good journalism died a long time ago, and the opinionated drivel that clogs the arteries of society is not worth my time and attention. We do however subscribe to a daily paper, just in case there is something major of which we need to be aware. Other than that, it’s Bizarro and Annie’s Mailbox which pretty much take me through my morning papaya. I always find it intriguing to discover what others deem critical enough to share on a national forum, and today it concerned a gal so repelled by her obese father that she just had to ask for help in managing her irritation. Annie’s response was that “Dad already feels worthless, so instead of anger and disgust, try compassion.” That got me going.

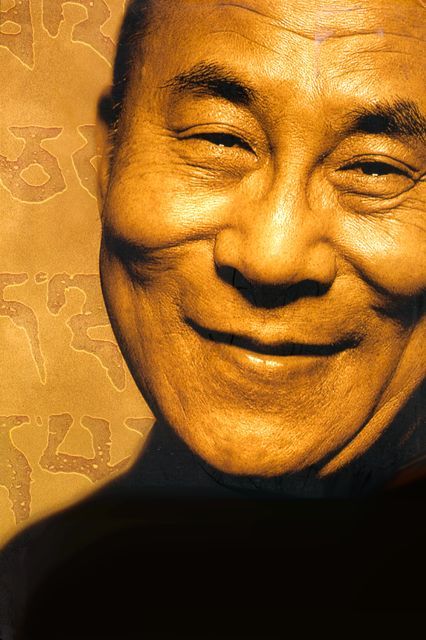

The term compassion gets tossed around a lot these days, with less regard than the word sympathy. To my mind, any of us can feel empathy or sympathy for another going through a tough time. Compassion, however, is a horse of a different color. Compassion itself has come to the fore largely due to the life work of such noble beings as the spiritual leader Tenzin Gyatso, more commonly known as Tibet’s 14th Dalai Lama. Even the Tibetans don’t toss the concept around lightly – they encourage a lifetime practice of sitting with ourselves in mindful meditation so that we might touch, among other things, the heart of genuine compassion.

You can understand how something this demanding differs from a sentiment like sympathy. Even Webster’s definition is dilute in its effort to express the depth of this character trait as the sympathetic consciousness of another’s distress together with a desire to alleviate it. Yet it becomes clear even then that this is simply not something we learn overnight. Sympathy or empathy are feelings that naturally arise when we observe another’s pain and can identify with it. Compassion derives from a committed inner practice and awareness of the pervasive nature of suffering itself. It is not a quality that can be elicited or forced before its time, much like the aging of a fine wine.

In typical Western fashion, many strive to attain overnight what Tibetan monks and nuns have achieved over a lifetime of dedicated service, having entered the monastic life as very small children. There’s nothing wrong with a desire to better ourselves, only let’s be realistic about what it takes to plumb the depths of our true being: a moment to moment awareness of our thoughts and intentions. Forgiveness of ourselves and others develops over time, where we discover what lies beyond inner walls of self hatred and blame.

Forgiveness itself may well be key, as most have someone or something hanging in that balance, and absolving ourselves can prove the most humbling of all. As we strive to bear no malice toward others – and this is not something we can simply say and it becomes so – we discover in the process that, in being sentient, we suffer. Awareness of this noble truth arises in an open heart. We begin to understand the lonely twisting pain of those who have wronged us – those who are not yet able to forgive others who have crushed their spirit and have little hope of exculpating themselves. And so in their ignorance, they pass it on. It is with an equal yet opposing force of determination that we may choose to commit ourselves to a path of peace, diligently cultivating the tenderness required for a compassionate existence. As Sogyal Rinpoche offers, “Compassion is not true compassion unless it is active.”